AN old man with a long straggly beard shuffles over the ancient mosaic floor, wearing an aged dressing gown and a floppy night cap. He sits at his desk and starts to dig into his long memory. He remembers the young boy with the long, thin fingers who was unsuited to the physically demanding farmwork of his peers. Gradually the years fall away, the boy’s intelligence and ability to read and write are recognised and he becomes a clerk in a Sturminster Newton office. His facility with words is useful, although his ability to rhyme will never make him rich.

AN old man with a long straggly beard shuffles over the ancient mosaic floor, wearing an aged dressing gown and a floppy night cap. He sits at his desk and starts to dig into his long memory. He remembers the young boy with the long, thin fingers who was unsuited to the physically demanding farmwork of his peers. Gradually the years fall away, the boy’s intelligence and ability to read and write are recognised and he becomes a clerk in a Sturminster Newton office. His facility with words is useful, although his ability to rhyme will never make him rich.

He falls in love with the daughter of a fairly well-off man who doesn’t seem keen on the match. He hears of a school at Mere that he can take over – he travels to this “London by the downs” but when he gets there, it is just a village and the school is long-closed. But this young man is William Barnes and he has resources of both intellect and mental strength that will see him through a long and remarkable life – much of it with his beloved Julia. Her father approves the match when he sees what a worthy young man she has found.

Nowadays, we mostly remember William Barnes as the Dorset dialect poet. Outside Dorset, he is perhaps not remembered much at all, beyond the rather rarified academic confines of ancient languages and philology. Barnes was fascinated by the roots of language and in his studies and researches he acquired a working knowledge of 70 languages. SEVENTY. Even as a very young man, before he started his school in Mere, he had mastered French, Latin, Greek, Persian and Hindustani. Throughout most of his life he kept a diary, which from the start he wrote in Italian!

Barnes not only loved and wanted to preserve the rather distinctive Dorset dialect which was still common in his youth, in the first half of the 19th century. He also believed that it was a true descendant of the Anglo Saxon that was spoken before the Norman Conquest.

Barnes not only loved and wanted to preserve the rather distinctive Dorset dialect which was still common in his youth, in the first half of the 19th century. He also believed that it was a true descendant of the Anglo Saxon that was spoken before the Norman Conquest.

Unlike his near contemporary, Thomas Hardy, Barnes never really became a celebrity. Royalty, authors and academics did not beat a path to his door. He had times of great poverty, but he had huge resilience, a deep faith and a long and happy marriage. He also imparted a wide education in the classics, mathematics, languages, botany and more to boys who would remember him as a great teacher. In later life, after he had taken holy orders following a divinity course at Cambridge University, and when Julia had died and his school had failed, he was rescued by a former pupil, the now successful Captain Damers, who gave him the living of Winterbourne Came with a rectory, for the rest of his life. He died in 1886 aged 85.

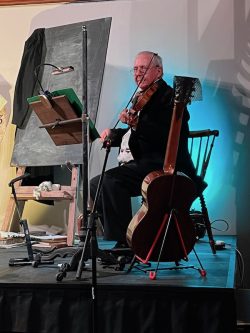

Tim Laycock first brought Barnes’ life story to the stage more than 20 years ago, in The Year Clock, a two-man show, with musician Colin Thompson. He and Colin have revived it this year for two performances, to raise funds for the William Barnes Society and the Dorset History Centre to catalogue and digitise the large Barnes archive which currently sits in many boxes at the history centre. Judging from the enthusiasm of the large audience that packed the beautiful Victorian hall in the Dorset Museum and Art Gallery in Dorchester, there should be a sizeable boost to the £30,000 target.

The play captures so much of what we may imagine Barnes to have been – kind, intelligent, observant, determined, warm-hearted, a lover of music and dancing, serious but never overly solemn … It is an appealing picture. In truth, he comes across as a much more attractive personality than Thomas Hardy, however great the better-known writer is as both a poet and novelist.

The play captures so much of what we may imagine Barnes to have been – kind, intelligent, observant, determined, warm-hearted, a lover of music and dancing, serious but never overly solemn … It is an appealing picture. In truth, he comes across as a much more attractive personality than Thomas Hardy, however great the better-known writer is as both a poet and novelist.

The second performance of The Year Clock is at the Exchange at Sturminster Newton on Sunday 3rd November at 3pm. If you saw Tim’s wonderful performance originally, refresh your memory and reacquaint yourself with the great legacy of William Barnes. If you have never seen it, this is a rare chance to learn a lot about a man who is so much more than the dialect poet who wrote Linden Lea.

FC